|

| Thomas Struth CHEMISTRY FUME CABINET UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH 2010 |

|

| Thomas Struth CURVED WAVE-TANK UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH 2010 |

"Unlike, for example, the gritty, dread-inducing paintings of Anselm Kiefer, whose thoughts never seem far from Auschwitz, Struth’s photographs evoke nothing bad. They have a lightness of spirit, you could almost say a sunniness, that is not present in the work of the other major practitioners of the new oversized color photography—Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer, Jeff Wall, Thomas Ruff among them. Struth is the Sunday child of the lot. His huge photographs—city streets, people looking at paintings in museums, industrial landscapes, factories, laboratories, rain forests, and family groups—are as pleasing as his persona; they seem to be an extension of it. Michael Fried, in his tautly argued book Why Photography Matters as Art as Never Before (2008), pauses to remark, with apparent (uncharacteristic) irrelevance — but evident intuitive understanding of the force of Struth’s radiance — “A striking fact about Struth’s public career is the almost universally enthusiastic response that his work has received.”

|

| Thomas Struth DRYDOCK DSME SHIPYARD, GEOJE ISLAND, KOREA 2007 |

|

| Thomas Struth FIELD-ION MICROSCOPE UNIVERSITAET, ZURICH 2010 |

|

| Thomas Struth PHARMACEUTICAL PACKAGING LABORATORIES PHOENIX, BUENOS AIRES 2009 |

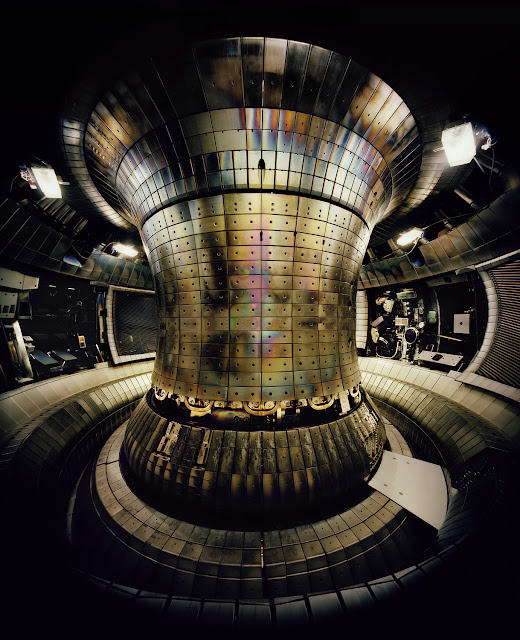

"Struth’s photographs taken in factories, laboratories, and nuclear power plants ... look like nothing one has ever seen before. These glimpses into what the critic Benjamin Buchloh calls “the technological sublime” were on view at Marian Goodman last year and constitute some of Struth’s most powerful images. ... The feeling of not understanding what one is seeing, of not knowing the functions of madly tangled wires and tubes and cables and mysterious flanges and pulleys and levers, is brilliantly conveyed by these huge pictures of places few of us have ventured into and on whose products many of us depend. Predictably, the places are not satanic mills but belong to the world of Struth’s benign photographic vision. They reassure even as they baffle. They tell us that the people who are absent from the pictures are back there somewhere and that they know what it all means and know what they are doing."

|

| Thomas Struth REACTOR PRESSURE VESSEL PHASE-OUT AKW WUERGASSEN, BEVERUNGEN 2009 |

|

| Thomas Struth SEEMLESS TUBE PRODUCTION TENARIS SIDERCA CAMPANA, BUENOS AIRES 2009 |

|

| Thomas Struth SEMI-SUBMERSIBLE RIG DSME SHIPYARD, GEOJE ISLAND,KOREA 2007 |

"The picture we had been standing in front of showed a semi-submersible oil rig in a shipyard on Geoje Island, in South Korea—a huge red thing, a colossus on four legs on a platform afloat near the shore, taut cables anchoring it to the concrete pavement onshore, on which piles of miscellaneous building materials are strewn. The photograph (a hundred and ten by a hundred and thirty-eight inches) magisterially represents what can be called the new optics of the new photography, which sees the world as no human eye does. When you look at these photographs, it is as if you were looking through strange new bifocals that focus on things at a distance at the same moment that they focus on things close up. Everything is equally sharp."

|

| Thomas Struth SPACE SHUTTLE KENNEDY SPACE CENTER, CAPE CANAVERAL 2008 |

|

| Thomas Struth STELLARATOR WENDELSTEIN 7-X DETAIL MAX PLANCK IPP, GREIFSWALD 2009 |

|

| Thomas Struth TOKAMAK ASDEX UPGRADE INTERIOR I MAX PLANCK IPP, GARCHING 2010 |

|

| Thomas Struth TOKAMAK ASDEX UPGRADE PERIPHERY MAX PLANCK IPP, GARCHING 2009 |

|

| Thomas Struth VEHICLE ASSEMBLY BUILDING KENNEDY SPACE CENTER, CAPE CANAVERAL 2008 |

|

| Thomas Struth Installation View 2010 Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin |

Quoted texts above are from Janet Malcolm's extended New Yorker interview with Thomas Struth published in 2011. This usually-skeptical journalist conveyed the impression that she – like the rest of the art world – felt spontaneously fond of the forthright and ingenuous Struth. Yet their concluding exchange, as reported below, also suggests that she had a few reservations. Malcolm describes herself strolling with Struth through Dresden, talking about the artist's most recent pictures shot at industrial and scientific workplaces. She asked if he felt he was making some sort of "statement" about society with these photographs.

"I think yes," he said, but he added, "Some of the pictures don't show what I was thinking. For instance, when I went to Cape Canaveral as a tourist I was struck with the sense of the space program as an instrument of power. When, as a state, you demonstrate that you are able to do that, it contributes to cultural dominance. I hadn't realized this before. But when I went there to photograph I saw that it is something you cannot put into a photograph."

"Do you feel you need to put large meanings into your work?" I asked.

"Well, it's part of my thinking. It's something that stimulates me. To have a narrative is an incentive. If it was only about composition and light and beautiful pictures, I could just photograph flowers."

"Forget the flowers," I said, "Let's stay in the factory. Because there were very beautiful forms there. Wouldn't that be enough for you? If you just found beautiful compositions there, and made beautiful photographic abstractions. You want to do more than that?"

"Yes."

"I'm trying to elicit from you what the more is."

"The more is a desire to melt, like to – how can I say it? – be an antenna for a part of our contemporary life and to give this energy, put that into part of this narrative of the visual, of sort of symbolic visual expression ..." Struth struggled, and gave up.

I asked him if the fact that SolarWorld's activity had to do with solar energy was part of his interest in photographing there.

He said that it was, and added, "My own personal energy account is very bad, because I fly so often and I can't claim that I'm a good sustainable-energy person. But I've almost always voted for the Green Party, and since it was founded I always thought these subjects were important and are a fascinating challenge for the world."

"How will your pictures show that what is being produced at SolarWorld is good for mankind?"

'"Just by the title."

"So photographs don't speak."

"The picture itself is powerless to show."