|

| August Allebé Head of Rhinoceros ca. 1870-84 drawing Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam |

|

| August Allebé Study of a cast of an antique Dancing Faun ca. 1855-60 drawing Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam |

"Meanwhile, pursuing his amours in secret, Raffaello continued to divert himself beyond measure with the pleasures of love; when it happened that, having on one occasion indulged in more than his usual excess, he returned to his house in a violent fever. The physicians, therefore, believing that he had overheated himself, and receiving from him no confession of the excess of which he had been guilty, imprudently bled him, insomuch that he was weakened and felt himself sinking; for he was in need rather of restoratives. Thereupon he made his will: and first, like a good Christian, he sent his mistress out of the house, leaving her the means to live honourably. Next, he divided his possessions among his disciples, Giulio Romano, whom he had always loved dearly, and the Florentine Giovanni Francesco, called Il Fattore, with a priest of Urbino, his kinsman, whose name I do not know. Then he gave orders that some of his wealth should be used for restoring with new masonry one of the ancient tabernacles in S. Maria Rotunda, and for making an altar, with a marble statue of Our Lady, in that church, which he chose as his place of repose and burial after death; and he left all the rest to Giulio and Giovanni Francesco, appointing as executor of his will Messer Baldassarre da Pescia, then Datary to the Pope. Finally, he confessed and was penitent, and ended the course of his life at the age of thirty-seven, on the same day that he was born, which was Good Friday. And even as he embellished the world with his talents, so it may be believed, does his soul adorn Heaven by his presence."

– Giorgio Vasari, from Lives of the Painters, Sculptors and Architects (1568), translated by Gaston du C. de Vere (1912)

|

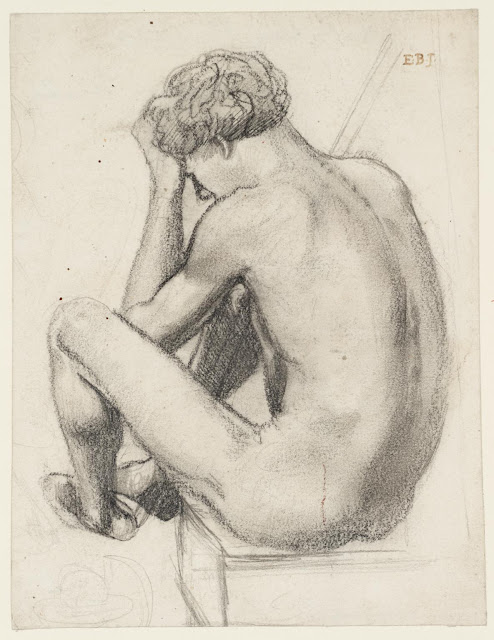

| Edward Burne-Jones Desiderium from The Faerie Queene 1873 drawing Tate, London |

|

| Edward Burne-Jones Study for The Liberation of Peter ca. 1863 drawing Tate, London |

Keep away, son, these lakes are salt. These flowers

Eat insects. Here private lunatics

Yell and skip in a very dry country.

Or where some haywire monument

Some badfaced daddy of fear

Commands an unintelligent rite.

– Thomas Merton, from Advice to a Young Prophet (1963)

|

| John Constable Self-portrait 1806 drawing Tate, London |

|

| Charles Samuel Keene Two artists working by lamplight in a studio ca. 1860 drawing Tate, London |

|

| William Mulready Study of hands 1860 drawing Tate, London |

|

| William Mulready Study of hands 1859 drawing Tate, London |

|

| William Mulready Study of hands 1861 drawing Tate, London |

|

| George Richmond Elijah and the Angel ca. 1824-25 drawing Tate, London |

Him thought, he by the Brook of Cherith stood

And saw the Ravens with their horny beaks

Food to Elijah bring Even and Morn,

Though ravenous, taught to abstain from what they brought:

He saw the Prophet also how he fled

Into the Desert, and how there he slept

Under a Juniper; then how awakt,

He found his Supper on the coals prepar'd,

And by the Angel was bid rise and eat,

And eat the second time after repose,

The strength whereof suffic'd him forty days;

– John Milton, from Paradise Regain'd (1671)

|

| Frederick Sandys Study of trees and undergrowth ca. 1855 drawing Tate, London |

|

| Alfred Stevens Study of kneeling youth bending a bow for decorative scheme at Dorchester House ca. 1860 drawing Tate, London |

|

| Aubrey Beardsley La Dame aux Camélias 1894 drawing Tate, London |